Poetry, Songs and Dance as Amazigh Strong Markers of Identity

Conquerors, colonizers and other foreign powers that to different extents have tried to override and reshape Amazigh identity, have influenced the Amazigh people of North Africa and the Sahel in the cultural expression and the freedom to preserve a unique identity. Due to an inherent need to be recognized as human, unique and valuable, Amazigh people have been using different forms of expression to celebrate and revive Amazigh culture. One of the major artistic expressions is performance art – song, dance, poetry and theatrical performances. Young Amazigh activists have been using these different forms of expression in order to reaffirm their identity but, also, as a wakeup call to not lose the riches of their culture.

Let us start from the premise that each individual as born into a certain community, society, and culture, wants to be recognized for who he is. The idea of identity can be tied to an individualistic view of the world, focusing on the freedom to express one’s own individual desires and needs within the society. However, identity is a combination of layers, informed by individual needs and wants but also by the drive to belong to some sort of community, which is again informed by cultures. Those cultures might be based on ethnicity, heritage, and language representing an anthropological frame or they might be based on identification with a certain interest group, age group, etc. Identity can be a personal acknowledgement, however, in this analysis we shall focus on the outward expression of identity, specifically through the art of performance – dance, song and poetry.

In a struggle for identity recognition, the Amazigh people of Morocco and Algeria have been expressing thier cultural belonging through various art forms. Famous for their oral tradition, the Amazigh culture is rich in poetry, lullabies, songs of varying content, riddles, and enigmas. Looking primarily at Anglophone research work by Michael Peyron, Jane E. Goodman and Cynthia Becker, a picture of a distinct performative tradition arises notwithstanding the fact that all forms of expression discussed are subject to regional and situational variations. This research work should provide an insight into the changing scene of Amazigh poetry, as well as performance arts of the Kabyle people in Algeria and the Ait Khabbash tribe in Morocco, without necessarily holding them against each other in comparison. It shall demonstrate how traditional arts are an expression of identity and cultural belonging and shine light on usage of performance and song to struggle for the recognition of identity.

Michael Peyron, former professor of Amazigh History and Culture at Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane, Morocco is a connoisseur of Amazigh poetry and song. He describes the change of meaning Amazigh poetry has undergone:

“From what used to be a mainstream oral literature genre in late-19th century Morocco, popular Tamazight poetry together with ballad-style epic and religious verse have, barely a hundred years later, definitely become an archetypal form of minority expression.”

His observation is a sign for the struggle of identity recognition of the Amazigh amongst the Arab-Islamic society. Often viewed as less cultured by the growing urban population, Amazigh people from the villages have resorted to expressing their resentment through poetry, recalling the “stirring achievements of their heroes, both during the resistance phase and in earlier centuries” . As Katherine Hoffman notes, the Ishelhin – the Amazigh people from the South-West of Morocco – use language differently in conversational speech than they do in poetic speech. A lot of value is thus given to poetic expression. Interestingly enough, the richness in expressions of poetic language has been preserved and continued in tradition – a tradition mainly carried on by women who are endowed with passing down culture and tradition.

Cynthia Becker’s extensive research on the role of women in Amazigh arts focuses specifically on the Amazigh from the Ait Khabbash tribe in Morocco. Her observations of the ahidous dance can be seen in the light of the earlier given framework of identity. Becker defines ahidous as a “collective performance at weddings and other celebrations that incorporate oral poetry”.This type of performance exists in many Amazigh groups, however varying in rhythm, steps, clothing and song techniques from group to group. She takes as an example the Ait Khabbash in comparison to the Imazighen of the High Atlas mountains; While the performances of the Ait Khabbash are initiated by men forming a line, women joining them in a parallel line facing the men, the performance of the Imazighen is organized in one line with men and women standing next to each other. This comparison makes clear that even though a group might identify with a vast culture in the anthropological sense, there are smaller entities of cultures that might have a tighter identity definition. In other words, the concept of belonging to a bigger entity of culture can be empowering – personally and politically, however it might also be less tangible due to little contact with members of the whole ethnic community.

One of the main reasons for the strong feeling of belonging to a smaller entity of culture can be the location. Since the ahidousare collective performances, they take place in the center of life in a village. Anyone in the village is invited to come – depending on the village it might even be an insult for the village community if somebody does not show up.

Also Jane Goodman, in her book: “Berber Culture on the World Stage – From Village to Video” makes a similar observation about the local wedding dance and its community value. She writes:

“The wedding or, more specifically, the evening dance known as the urar, is the only place where almost everyone present in the village shows up at the same time.”

Even though the dancers and musicians can be subject to critique by their fellow dancers/musicians or the audience, the learning process is informal and ongoing. These observations suggest that the access to identity through performance and dance is a given due to the dances taking place in a public space and due to their invitation that extends to any member of the community.

During a trip to Zawyat Ahnsal, I observed and participated in a music and dance performance at the house of the local sheikh. The circle in which we danced was so tight that learning the steps was imperative in order to avoid disturbing the rhythm and flux of the dance. However, standing very close to the ladies in the circle, I also learned the steps quickly since I was literally taken by the shoulder, swayed up and down. The physical vicinity of people dancing clearly enhances a feeling of belonging, of metaphorically and literally breathing together. Quite interestingly, the local women of Zawyat Ahnsal built a second circle by themselves, not joining the already existing circle of musicians with little wooden framed drums. The circle of male musicians increased in size with every visitor squeezing in between local dancers – here not adhering to a segregation of gender.

Becker makes similar observations of gender segregation through dancing in different circles but also through a veil that covers the women’s faces. Becker links this phenomenon with the influence of the Arab world in the 1960s:

“. . . social pressure from Arabs in the 1960s and increased exposure to Islamic modesty requirements caused their previously nomadic ancestors to modify ahidous to include the head covering as a physical barrier between unrelated men and women facing each other during the performance.”

Becker also notes differences in dancing and suggests that the women originally took bigger strides in their ahidous dance but are now restricted by social conventions. She bases her assumption on the observation and comparison between the heavily populated area of Tafilalet versus more rural areas, imagining that the style in the remote villages has been better preserved from the past. Similarly, Goodman also notices gender segregation amongst the Kabyle Amazigh, where urars are watched by the audience divided into men and women sitting on different sides of the dance space.

Especially with the influence of a western dominated media blaming issues of gender inequality on Islam, Amazigh activists often stress the original matriarchal social order of Amazigh tribes. Therefore, supporting a struggle for identity recognition using Western agenda and reverting it back against the predominant Arab-centric Islamic interpretation.

However, in Amazigh culture, women still occupy a special place in society. Being the center of family life, women are also the bearers of culture and tradition, passing down to their children knowledge of poetry, folk tales and song. Similarly to men who can recite the entire Qur’an, there is a term for women who are well versed in Amazigh poetry. Women are the ones who are the main resources to researchers as well as Amazigh youth who have lost touch with their roots. Women are therefore very powerful in helping to preserve some of the oral traditions that are not completely noted down. Women are also active in writing poetry themselves. A valid example for women poets is Mririda n-Ayt ‘Attiq, from the Tassawt area in Morocco. French national René Euloge recorded and translated her poems into a book of poetry. N-Ayt ‘Attiq’s poetry reaches a wide arrange of themes, from love poetry to nature, human relationships, land ownership, conflicts, youth, marriage and death.

On the issue of gender, young Kabyle activists have been staging new kinds of theatrical performances. These performances center around everyday life activities such as meetings.

“For them, performances operated as sites of heightened reflexivity (…) through which they could critique prevailing forms of social organization and experiment with new identities.”

The development of using a Western narrative to address the need for the recognition of Amazigh identity and in some more radical cases, the longing for independence from an Arabic state can also be seen in Algeria. Goodman’s research on the Kabyle Amazigh of Algeria sheds light on political attempts to drift away from a leadership that patronizes Amazigh heritage, not considering it of high value. She points out the problems with the Algerian struggle for independence against the French colonial power:

“The longing for liberation of the Algerian people led the Front de Libération Nationale to stress a sense of unity and uniformity rather than individual identities of its diverse ethnic groups.”

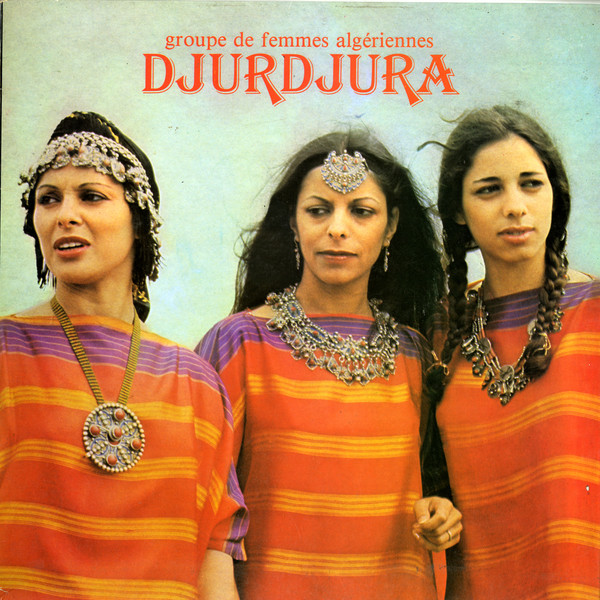

In search for a purist Amazigh identity, not touched by foreign rule, poets have been retrieving old folklore. The revival of Amazigh song and its publication happened mainly through Amazigh radio stations. In her extensive research on staging Amazigh culture in Algeria Jane E Goodman detects a relatively young tendency for Amazigh activists to modernize Amazigh poetry and song while emphasizing their traditional value. She specifically looks at the work of two famous poets/musicians – Ben Mohamed and a singer by the artist name of Idir. In their political activism for the recognition of Amazigh identity, they molded traditional song texts into politically motivated texts, appealing to a new generation and motivating this generation to become politically active for their own cultural identity. Also the music itself was transformed in order to a younger style by “lightening up slow rhythms and tempos”.

What was of central importance to Idir and Ben Mohamed was certainly their extensive knowledge of traditional music as well as texts, a requirement to avoid distorting authenticity. Comparing song lyrics by Ben Mohamed to older versions of the same songs, Goodman notices the omission of religious connotations or religious phrases in Ben Mohamed’s new interpretations. Ben Mohamed believes that “the essential is said in two lines, then you start with a religious thing . . . and it’s just to garnish” . Due to a tendency for Amazigh activism to be less religiously motivated, Ben Mohamed’s response might be only a part of the real reason for his taking out religious phrases. Here again, the yearning for cultural and social appreciation without a religious connection becomes apparent and is a valid example for the struggle for identity recognition of an underrepresented ethnicity that is proud of their heritage, including Pagan traditions.

The tendency for purism in Amazigh activism shines through in the extensive search for original words in different Amazigh dialects like Tashelhit and Tamazight. Even though village life has been dynamic and influenced by outside and inside changes, Amazigh activism very much focuses on anything ancient and sometimes outdated in actual Amazigh villages. Language used in revisions of Amazigh poetry is a clear indicator for this phenomenon. As a result, Amazigh poetry is replete with nostalgia for a past era. Ideas of life as it used to be are idealized and the idea of the village and typical Amazigh households have gained an almost mythical value. An idealized village is passed on as cultural heritage while its development plays a secondary role.

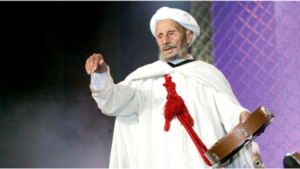

The purist idea of stripping Amazigh culture of foreign influences – mainly Arab-Islamic – stands in contrast to an observation of an Amazigh performance in the area of Azrou, Morocco. During a dance and music performance for the group’s entertainment, the dancer moved in a very particular style, with positions almost kneeling, holding his pose stretching his arms diagonal to the ground. Michael Peyron believes that the style is prevalent in the area of Azrou, Imzouane and Ifrane and relatively new invention by, The world-famed “Maestro” Moha Oulhoussain Achibane. Unlike the belief that Amazigh culture mainly lives in the past, the “Maestro” is proving the opposite mainly that the culture is alive and well, and even more: it is developing and in flux.

Also poetry and song are filled with new developments, not only by new interpretations of poets like Idir and Ben Mohamed. Improvisation is a very common occurrence in Amazigh performance. Since poetry, stories and songs are still orally passed down generations, Amazigh heritage is preserved while it is reshaped by the new generations. Frequent discussions during the performance of a song are common according to Goodman. She recalls:

“Between some verses [the women] briefly paused for discussion. At one point . . . one young women said: “That’s all”; the older woman disagreed and went on to sing several more verses.”

Also Becker denotes that there is a prevalence of the older generation being better at “playing” ahidous, the afore-mentioned dance performed at weddings and other celebrations amongst the people of the Ait Khabbash.

Conclusion

Ultimately, no matter what the connection may be, whether through dance, theater, song or poetry, Amazigh people deserve to be recognized as who they identify with, a unique and rich culture. The arts are a pathway to political activism, questioning notions of new and old changes, keeping the culture alive and dynamic.

Dr. Mohamed Chtatou is a senior professor of business communication at the International University of Rabat -IUR- as well at Mohammed V University in Rabat. He is currently a political analyst with Moroccan, Gulf, French, Italian and British media on politics and culture in the Middle East, Islam and Islamism as well as terrorism.